ShopDreamUp AI ArtDreamUp

Deviation Actions

Description

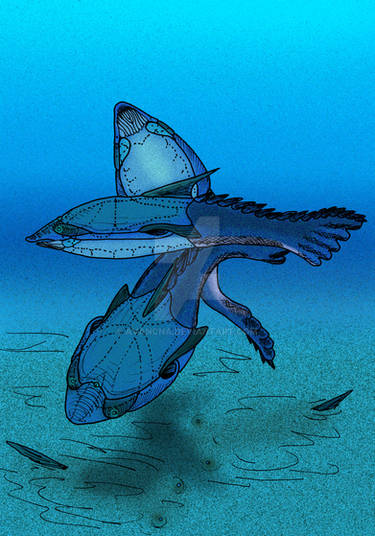

Common leftjaw, Volaticus inequalis, on emergent tree branch and orbulescent algae colonies. The single erupted upper incisor of the leftjaw, used to bore out insect larvae from trees, is the left one more than 98% of the time; rarely, the right one may also erupt, producing a double-tusked animal, but almost never does the right tusk erupt alone.

Another redo.

~~~

Farkles are an unusual subfamily of predominately arboreal Theropodents native to the Aenvarnan rainforest notable for their highly-developed gliding adaptations, which in some forms have given rise to very primitive powered flight, and, in some species, their spectacular and often visibly unsymmetrical dentition. Ranging in size from the two-pound Lesser Glidia to the large Glubchuck, which is too large to glide and feeds on the forest floor, they are all generally regarded as the simultaneously most basal yet most specialized living members of the Bronkjird family and the only subfamily of this clade to have specialized entirely on consuming animal matter versus vegetation. All farkles, large or small, or mainly insectivorous, and often rely on highly specialized tusked incisors to probe tree park or packed soil for hidden insect prey, either by directly digging them out in the manner of a woodpecker's beak or tapping the trunk to hear for vibrations, like an eye-eye's fingers. Different species of Farkle even within one genus may exhibit radically different teeth, symbolizing different prey preferences, with dual teeth that just outwards like a pick ax to break up rotten wood or a single corkscrewed fang on just one side of the mouth adapted to drill through healthy, harder wood. Some species have a thin, curved tooth to hook grubs from their burrows and still others have no specialized teeth at all, being generalists and instead catching their prey on open leaves and branches or upon the ground. All Farkles retain the strong, grinding molars of their ancestors and use them to crush and chew their prey thoroughly before swallowing it, in direct contrast to the gulping habits of the Tyrannorats. A handful of mainly terrestrial species specialize in this regard, feeding themselves by crushing snails and molluscs near the seashore.

The wings of a farkle are formed by the webbing of the third, fourth, and fifth fingers in the hand, somewhat alike the wings of a bat. The first digit is entirely absent, as in all theropodents, while the second finger forms a semi-opposing thumb. The specialization of the wings is variable across species and genera, with some species exhibiting very broad membranes for long-distance gliding while others show thinner, elongated wings suited to high-speed gliding and turning. Most Farkles are capable of flapping their wings to prolong their glides, but only one genus, Volaticus, has both a strong enough wingbeat and a large enough membrane to propel itself to any extent without a gliding start. Members of the Volaticus genus, which are all specialized with long, foreword-jutting single or double tusks, are capable of slow, awkward flight for distances of up to a hundred meters from the ground or almost indefinitely down gradually sloping terrain when assisted by the wind, though they prefer to run or climb for cover when pressed.

Some farkles which have highly specialized to glide rather than fly have well-developed hind wings derived from an elongated fifth toe connected via a small patagium to the long, broad tail which increase their surface area and allow for longer downward flights. This may be an ancestral trait, with a remnant uropatagium and slight hind wing membrane being present in most species. Species which spend a lot of time on the ground exhibit the smallest hind wings, while the most arboreal species which rarely run have the most prominent. The innermost hind toe of all farkles, vestigial in many other bronkjirds, is semi-opposed and midway through a plausible evolutionary path to a reversed hallux like that of the birds, an adaptation to perching.

~~

Orbulescent Algae

Orbulescent algae are a unique colonial variation of Cladophora algae which have evolved to produce hydrogen gas through their day to day process of photosynthesis and to store it in spherical membranes formed by their billions of interconnected cells, allowing the colonies to float, lighter than air, tethered via root-like cords like living balloons above the jungle treetops. Occuring only in a relatively small range near the extreme south pole in the upper canopy of the Aenvarnan rainforest, they originate from an aquatic ancestor which occurs in significant numbers on our own planet and also forms spherical colonies. How the algae made the jump from sea to land originally isn't entirely known, though it may have been an adaptation of colonies to survive in poorly-oxygenated bodies of water, who reached the surface by filling the centers of their colonies with the gas to float to the surface, eventually producing enough to leave the water and float on the air to populated new bodies of water. Today, the algae are rare and occur only in isolated environments, but where conditions are favorable - extremely humid and mild, with little wind - they can grow to more than eight meters across. Reproduction occurs mainly via budding, with new colonies forming on the wiry stalks of old and blowing away on the breeze until they tangle their tendrils on a new branch - something that occurs relatively rarely with success, as is demonstrated by the low population density of colonies.

Orbulescent algae colonies on Sheatheria as a whole are little-understood. Though they appear highly primitive, when operating as a single ballont, the algae are capable of remarkable awareness and can actively respond to their environment. When the air pressure drops dramatically shortly before a storm rolls in, the algae respond by collapsing their cell walls, producing billions of tiny perforations in the sphere and dissipating the gas within harmlessly into the atmosphere to let themselves come gently to rest out of the open air and avoid being struck by lightning, which for a hydrogen ballont would be an explosive disaster. When the air pressure rises again and the sky clears, the algae restore their rigidity and rapidly inflate themselves again to proper form in as little as a few hours. When threatened by an herbivorous animal the colony can respond by dissipating small amounts of the precious gas from their pores in the form of hydrogen sulfide - a foul-smelling and toxic chemical responsible for the rotten odor of spoiled eggs - which is sufficient to deter even the hungriest browser from taking a bite. In the event the gas bag is ruptured, it can heal itself within a day by the accumulative efforts of the remaining cells to join back together, and if a colony is severely damaged, individual portions of the sac can reshape themselves into a new sphere and regain bouyancy in as little as ten hours, remarkable for organisms individually too small to see with the naked eye. To the touch, orbulescent algae colonies are soft and fuzzy, like shag carpet, and they are an ideal medium for smaller epiphytic plants and fungi to take hold upon, with old colonies eventually becoming too heavy to float as a result of their passengers, hanging from sturdy holdfasts from canopy trees and bouncing leisurely in the open air like enormous tetherballs, or slowly falling to Earth to be crowded out by more aggressive flora on the unforgiving ground.

Another redo.

~~~

Farkles are an unusual subfamily of predominately arboreal Theropodents native to the Aenvarnan rainforest notable for their highly-developed gliding adaptations, which in some forms have given rise to very primitive powered flight, and, in some species, their spectacular and often visibly unsymmetrical dentition. Ranging in size from the two-pound Lesser Glidia to the large Glubchuck, which is too large to glide and feeds on the forest floor, they are all generally regarded as the simultaneously most basal yet most specialized living members of the Bronkjird family and the only subfamily of this clade to have specialized entirely on consuming animal matter versus vegetation. All farkles, large or small, or mainly insectivorous, and often rely on highly specialized tusked incisors to probe tree park or packed soil for hidden insect prey, either by directly digging them out in the manner of a woodpecker's beak or tapping the trunk to hear for vibrations, like an eye-eye's fingers. Different species of Farkle even within one genus may exhibit radically different teeth, symbolizing different prey preferences, with dual teeth that just outwards like a pick ax to break up rotten wood or a single corkscrewed fang on just one side of the mouth adapted to drill through healthy, harder wood. Some species have a thin, curved tooth to hook grubs from their burrows and still others have no specialized teeth at all, being generalists and instead catching their prey on open leaves and branches or upon the ground. All Farkles retain the strong, grinding molars of their ancestors and use them to crush and chew their prey thoroughly before swallowing it, in direct contrast to the gulping habits of the Tyrannorats. A handful of mainly terrestrial species specialize in this regard, feeding themselves by crushing snails and molluscs near the seashore.

The wings of a farkle are formed by the webbing of the third, fourth, and fifth fingers in the hand, somewhat alike the wings of a bat. The first digit is entirely absent, as in all theropodents, while the second finger forms a semi-opposing thumb. The specialization of the wings is variable across species and genera, with some species exhibiting very broad membranes for long-distance gliding while others show thinner, elongated wings suited to high-speed gliding and turning. Most Farkles are capable of flapping their wings to prolong their glides, but only one genus, Volaticus, has both a strong enough wingbeat and a large enough membrane to propel itself to any extent without a gliding start. Members of the Volaticus genus, which are all specialized with long, foreword-jutting single or double tusks, are capable of slow, awkward flight for distances of up to a hundred meters from the ground or almost indefinitely down gradually sloping terrain when assisted by the wind, though they prefer to run or climb for cover when pressed.

Some farkles which have highly specialized to glide rather than fly have well-developed hind wings derived from an elongated fifth toe connected via a small patagium to the long, broad tail which increase their surface area and allow for longer downward flights. This may be an ancestral trait, with a remnant uropatagium and slight hind wing membrane being present in most species. Species which spend a lot of time on the ground exhibit the smallest hind wings, while the most arboreal species which rarely run have the most prominent. The innermost hind toe of all farkles, vestigial in many other bronkjirds, is semi-opposed and midway through a plausible evolutionary path to a reversed hallux like that of the birds, an adaptation to perching.

~~

Orbulescent Algae

Orbulescent algae are a unique colonial variation of Cladophora algae which have evolved to produce hydrogen gas through their day to day process of photosynthesis and to store it in spherical membranes formed by their billions of interconnected cells, allowing the colonies to float, lighter than air, tethered via root-like cords like living balloons above the jungle treetops. Occuring only in a relatively small range near the extreme south pole in the upper canopy of the Aenvarnan rainforest, they originate from an aquatic ancestor which occurs in significant numbers on our own planet and also forms spherical colonies. How the algae made the jump from sea to land originally isn't entirely known, though it may have been an adaptation of colonies to survive in poorly-oxygenated bodies of water, who reached the surface by filling the centers of their colonies with the gas to float to the surface, eventually producing enough to leave the water and float on the air to populated new bodies of water. Today, the algae are rare and occur only in isolated environments, but where conditions are favorable - extremely humid and mild, with little wind - they can grow to more than eight meters across. Reproduction occurs mainly via budding, with new colonies forming on the wiry stalks of old and blowing away on the breeze until they tangle their tendrils on a new branch - something that occurs relatively rarely with success, as is demonstrated by the low population density of colonies.

Orbulescent algae colonies on Sheatheria as a whole are little-understood. Though they appear highly primitive, when operating as a single ballont, the algae are capable of remarkable awareness and can actively respond to their environment. When the air pressure drops dramatically shortly before a storm rolls in, the algae respond by collapsing their cell walls, producing billions of tiny perforations in the sphere and dissipating the gas within harmlessly into the atmosphere to let themselves come gently to rest out of the open air and avoid being struck by lightning, which for a hydrogen ballont would be an explosive disaster. When the air pressure rises again and the sky clears, the algae restore their rigidity and rapidly inflate themselves again to proper form in as little as a few hours. When threatened by an herbivorous animal the colony can respond by dissipating small amounts of the precious gas from their pores in the form of hydrogen sulfide - a foul-smelling and toxic chemical responsible for the rotten odor of spoiled eggs - which is sufficient to deter even the hungriest browser from taking a bite. In the event the gas bag is ruptured, it can heal itself within a day by the accumulative efforts of the remaining cells to join back together, and if a colony is severely damaged, individual portions of the sac can reshape themselves into a new sphere and regain bouyancy in as little as ten hours, remarkable for organisms individually too small to see with the naked eye. To the touch, orbulescent algae colonies are soft and fuzzy, like shag carpet, and they are an ideal medium for smaller epiphytic plants and fungi to take hold upon, with old colonies eventually becoming too heavy to float as a result of their passengers, hanging from sturdy holdfasts from canopy trees and bouncing leisurely in the open air like enormous tetherballs, or slowly falling to Earth to be crowded out by more aggressive flora on the unforgiving ground.

Image size

1677x987px 371.62 KB

© 2016 - 2024 Sheather888

Comments2

Join the community to add your comment. Already a deviant? Log In

Its head looks very much like a rabbit (except it has tusks), I'm just saying.